The biggest lie of the agile metodology

21/07/2025

The biggest lie in the software industry is right in front of our eyes, yet nobody seems to notice it.

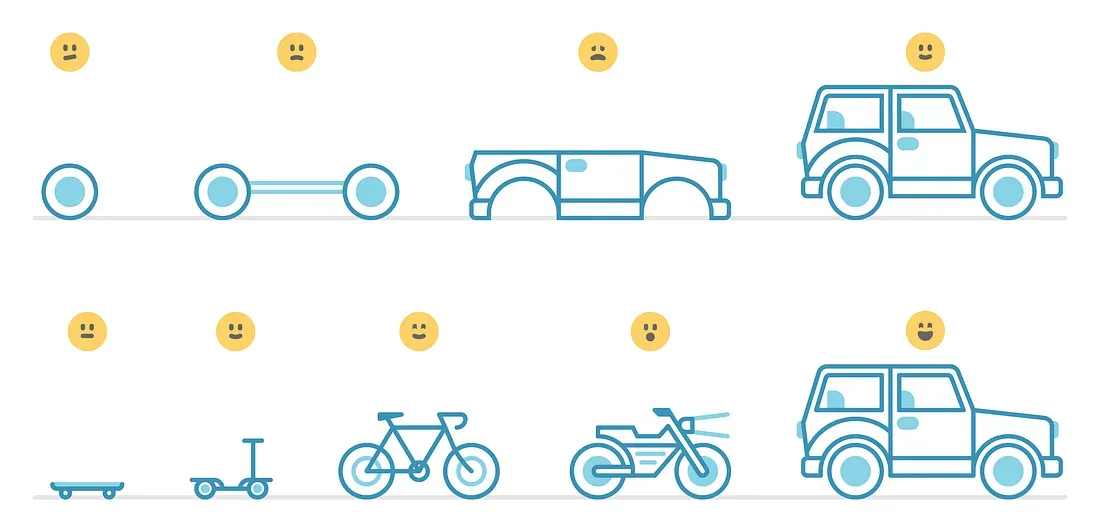

Forget for a second that we’re talking about software. Imagine you’re a mechanical engineer and someone shows you this picture. You’d laugh. Out loud. It’s absurd. Yet, for some reason, this “skateboard-to-car” diagram is the gold standard in our industry, burned into the collective subconscious. Nobody even blinks when they see it.

And maybe you’re wondering what my problem is. Is it the color palette? The corporate vibe? AI?

In theory, the concept sounds great: build an MVP as fast as possible, iterate, and improve. What could go wrong?

The Mechanical Engineer Problem

Let’s play this out in a mechanical engineering scenario. The client says they need a car. Following the agile MVP mantra, we deliver a bicycle. The client isn’t thrilled, but we tell them, “Don’t worry, we’ll get to the car.” Next, they ask for an engine. We strap one onto the bicycle and now we’ve got some sort of motorcycle. So far, so “agile”.

Then they ask for the car. “Four seats, four wheels, 0 to 300 km/h in 10 seconds, a trunk with 5 tons of capacity, you know, the usual.” The sales team promises it’ll be delivered in the next sprint and forwards the request to engineering.

The conversation goes something like this:

Sales: “The client wants a car. Next sprint, just like the motorcycle.”

Engineering: “We need a new engine, frame, wheels… basically a new project. This can’t happen in one sprint.”

Sales: “The client says they already paid for the engine and wheels, so just add two more wheels and make it work. One sprint, right?”

The engineering team, in a moment of desperation, zip-ties two motorcycles together, slaps on hardcoded doors that don’t open, and calls it a car. The client is unimpressed, but we tell them, “This is just the first iteration. The next one will be great.”

Where the Pain Starts

From here, it’s downhill. The engineers know they’ll never deliver a proper car without starting over, but the client thinks they’ve already paid for everything. To them, the dream car is just a few Jira tickets away.

The original engineers burn out and leave. New ones arrive with fresh hope, unaware of the monster that awaits. The remaining team watches with guilt, knowing exactly what this codebase will do to those innocent souls.

I’ve seen this too many times. Nobody knows how half of the code works anymore. There are comments that read don’t touch this. The linter begs for mercy. TypeScript stares at you from the corner, mumbling thousands of errors that will somehow still transpile. You can see the pain in every commit, every function, as the developers slowly lose touch with reality.

Why Does This Happen?

Because we believe software is infinitely adaptable, that we can just “reuse” and “refactor” everything at no cost. But every “innocent” client request has a price in time, in quality, or in both.

When developers don’t know where the product is ultimately headed, they can’t plan for it. Instead, the product evolves into something condemned to extinction, like a panda species that only eats bamboo and reproduces on the 32nd of November in prime number years. By the time someone asks why Vercel is billing us for two metric tons of bamboo, it’s already too late.

The Solution?

We’re not ready for a perfect solution as an industry. But at the very least, we need to be honest with clients: You can’t start with a bicycle aiming for a car, and then midway through demand an F-22 fighter, expecting everything to go smoothly.

Software development isn’t magic. You can’t duct tape your way from a bike to a sports car, no matter how many sprints you run or buzzwords you throw at the problem. Building great products means making real decisions early on about scope, architecture, and direction, and sticking to them long enough to avoid creating another eldritch horror. If we want to stop shipping ziptied motorcycles with fake doors, we need to start being honest with ourselves, with our teams, and with our clients. Otherwise, we’re just slowly drilling holes in our own heads like a babirusa, one sprint at a time.